- Home

- Shania Twain

From This Moment On Page 2

From This Moment On Read online

Page 2

Because of the unpredictable periods of instability in my childhood home, I didn’t feel that I could really rely on my parents to be consistent caregivers or protectors of me. I didn’t know what to count on from one day to the next—calm or chaos—and this made me anxious and insecure. It was hard to know what to expect, so it was easier to just be ready for anything, all the time. But I understand and forgive my parents completely for this because I know they did their best. All mothers and fathers have shortcomings, and although there were circumstances during my childhood that to some may seem extreme, if one could say my parents failed at times, I would say they did so honestly. They were often caught up in circumstances beyond their control. If my parents were here today, I’d tell them what a great job they did under the conditions. I would want them to feel good about how they raised me. I would thank them for showing me love and teaching me to never lose hope, to always remember that things could be worse and to be thankful for everything good in my life. Most important, they taught me to never forget to laugh. I thank them for always encouraging me to look on the bright side; it’s a gift that has carried me through many challenges. They may not always have been the best examples, or practiced what they preached, but it was clear they wanted better for us. That in itself was exemplary.

Ultimately, I am responsible for how I live my life now, and what I make out of it. In fact, I am actually grateful for what I’ve gone through and wouldn’t change a thing—although I admit I wouldn’t want to live it over again, either. Once was enough.

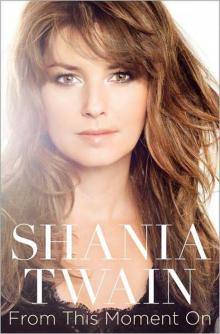

From This Moment On

1

SoThat’sWhat Happened to Me

Eileen Morrison waits to meet her newest grandchild, her only daughter Sharon’s second baby. It’s a hot summer day, and Sharon is in labor. She’s a bird-framed twenty-year-old with long, skinny legs, a pale face as bony as her knees, and a sharp nose. Agile and double-jointed, especially in the hips, Sharon has spent years doing gymnastics. She is a chatty, energetic young woman who enjoys telling of her amazing flexibility, like how she can cross her legs around the back of her neck or stand with them slightly straddled, bend all the way back, and with no hands pick up a rag placed on the floor between her feet. With her teeth. Sharon is warm, kind, and quick to laugh, in a loveable, widemouthed, high-pitched cackle.

Sharon’s delivery is long and complicated, with not enough relief for her pain. No epidural. The obstetrician’s voice betrays little hope as he informs her that the baby is breech, no longer moving, and is still in the birth canal. When she is finally delivered, there is no sound, no movement, no life.

While Sharon lies on the delivery table, the doctor quietly hands her a cigarette and lights it. That’s right: a cigarette, in the delivery room. The young woman understands that she has to be prepared for the worst. She’s delivered a blue baby, stillborn.

Except, miraculously, the baby girl is alive! Even more remarkable, she will have suffered no ill effects from the temporary lack of oxygen during the stressful delivery. (Not to mention the smoky delivery room!)

While I was growing up, my mother used to frequently tell me the story of my turbulent, dramatic entrance into the world—the worst of her four deliveries, she always said. Looking back, sometimes I can’t help but think to myself, So that’s what happened to me. Ha! It explains a lot.

In this smoky Canadian delivery room on August 28, 1965, I was born. The same year the Rolling Stones had their first number one hit, “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction,” Malcolm X was assassinated, and the movie musical The Sound of Music was released. My birth wasn’t as noteworthy as the more history-making moments taking place that year, but for my mother, a miracle had happened. We both survived that difficult birth.

I was named Eilleen Regina Edwards: Eilleen, after my mother’s Irish-born grandmother, Eileen Morrison; and Regina, after my biological father’s mother, whom we called Grandma Edwards. My grandmother Eileen was born in County Kildare, Ireland, to English parents named Lottie Reeves, from Wales, and Frank Pierce, from England. While my grandmother was still a small child, the Pierces migrated to Piney, Manitoba, to begin farming. I haven’t personally investigated the Edwards family genealogy myself, but my understanding of what my mother explained is that they had a mixed background of French-Canadian and Native Indian. And since the name Edwards originated in England, it’s possible they may have been British at some point in their family background. The exact percentages of which blood on whose side is a bit of a mystery, as is the case for many Canadians. The first European explorer to reach Canada, the Italian navigator Giovanni Caboto (better known from school textbooks as John Cabot), is believed to have landed in Newfoundland in 1497. Over the coming centuries, explorers from many nations around Europe followed, and the melting pot between Europeans and Native Canadians began, which is pretty much what I am a product of. I wouldn’t feel as though I were exaggerating in saying I’m quite the Heinz 57, considering the cross of so many nationalities over the centuries.

My mother, Sharon May Morrison, had a difficult life. When she was sixteen, she lost all of her teeth in an accident at school while crouched behind home plate playing catcher (or back catcher, as we call it in Canada) during a softball game. A batter swung mightily at a pitch and connected. As he took off toward first base, he flung the heavy bat behind him—smack dab into Sharon’s face, knocking her out cold. Most of her teeth were shattered from the blow. Reconstructive techniques weren’t as sophisticated as they are today, and so the only solution to giving her anything to smile about (or smile with, for that matter) was to pull out even the few remaining undamaged teeth and fit her for dentures. One can only imagine her horror as a teenage girl, regaining consciousness and discovering that her teeth were gone and her smile would never be the same again. I’m sure she must have felt robbed of her youth, to some extent. False teeth are for grannies, not adolescent girls, who are so self-conscious about their appearance as it is, and for whom life should be full of reasons to smile.

At eighteen, Sharon fell in love and got engaged. She was expecting her first child with her fiancé, Gilbert, but he was killed in a car accident shortly before my older sister, Jill, was born. The following year, 1964, my mother met and married my biological father, Clarence Edwards. I was their first child, followed two years later by my little sister, Carrie-Ann. My mother and Clarence divorced when I was still a toddler. From the one faded photograph my mother kept from their wedding day, I formed a vague impression of my father. He was a fairly short man, with an olive complexion and dark hair. I could tell from the photograph that both Carrie and I inherited his eyes, hazel green and almond shaped, as, clearly, we didn’t have the small, round, chocolate eyes of our mother. I was curious about him: to see the color of his eyes up close, to hear what his voice sounded like, to know his personality, but I didn’t know him or develop an attachment, and I didn’t miss someone I didn’t know.

Growing up, I knew he existed, that he apparently never had any other children, didn’t remarry but had a longtime girlfriend with children of her own, that he worked as a train engineer, lived in Chapleau, and had five or six siblings. I did often wonder what he thought of me and if he cared. I believed he probably did, as my mother told me it was more my father Jerry’s wish for Clarence not to be a part of our lives to avoid confusion in the family. Jerry was the one toiling with the day-to-day challenges of raising kids that weren’t his own, and he expressed his feelings clearly in regard to choosing one or the other—that I couldn’t have both fathers in my life. I accepted that as being fair enough.

The divorce between my mother and Clarence left her a single parent with three little girls. She turned to her mother for support, and we moved into my grandmother Eileen’s tiny farmhouse just outside of Timmins, in a small district called Hoyle. I don’t remember my grandmother working outside the home, but I do recall my mother having the odd waitressing and cashier job for short periods of time. But otherwise she was at home with us girls. Being a single mother in

the 1960s was not a desirable position to be in, as it wasn’t common for young women to further their education and become professionals, able to earn enough to provide for a family. Ideally, most girls finished high school, got married to a good provider, and started having children. This was the norm, and my mother was clearly well outside that norm.

My mother had little family in Ontario: only one brother in Timmins with five children of his own. The rest of her relatives still lived out west, where our great-grandparents had originally settled after emigrating from Ireland.

By the time my mother started having children of her own, my grandmother had long been a widow to my grandfather George Morrison. He had become terminally ill with a severe case of gangrene to his legs when my mother was still quite young. She was raised alone with my grandmother because her older brother was fifteen years her senior and was gone from the house when my mother was still a small child.

Grandma Eileen was pretty: fair skinned, with exotic blue eyes and pronounced cheekbones. She was tall and slender but had a heavier frame than my mother, who took after her thin, brown-eyed father. My grandmother genuinely possessed both inner and outer beauty and had a warm way about her that made me feel safe and nurtured. She was the one who filled the house with a calm concern for everyone.

I remember my grandma making us Cream of Wheat cereal, which she’d boil to lumpless perfection and serve up with brown sugar and fresh whole milk delivered each morning by the milkman. Grandma was good at keeping the house in order, like making sure our sheets and pillowcases stayed fresh, and there was always something baking in the oven, like bread, pie, or butter tarts. She used to leave her pies to cool on the windowsill, just like I’d see the women do in TV commercials for Crisco shortening. Her blueberry and apple pies were especially delicious. Blueberry pie was my favorite of the two. The berries were ready for picking only during a short period, from mid-July to early August, which made them even more special, since we weren’t able to get them any other time of the year. A fresh, warm slice was my much-deserved reward for my long mornings of picking the tiny berries and then suffering the runs from eating more from my pail than I actually took home. Oh, how I miss those blueberry pies!

To help pass the time waiting for the pies to cool, I’d play out in the fields with my sisters, running through the tall, golden grass, and I felt like a child that might have lived on the set of 1960s TV programs like Green Acres or Bonanza. I was happy and liked life. The fields were not owned by my grandmother, but they butted right up to the little farmhouse we lived in, as if they belonged to us. Summer seemed long in a good way at the farmhouse in Hoyle.

Are these warm, fuzzy memories from my first five years what I want to remember? Or was it really that nice when my grandma Eileen was with us? I’m not sure, but I believe that it probably was that good, since I’ve heard only nice things about her from anyone who ever knew her. More than the details, I especially remember feeling cared for and content when my grandma Eileen was there.

My sister Jill, two years older than me, was the first to start school. I can remember watching her enviously, my nose pressed up against the living room picture window, as she’d walk down to the end of the driveway to catch the school bus. I was excited for her but felt left out; I wanted to go, too. Even then, at the age of three or so, I craved independence and felt the urge to head out somewhere new. As far back as I can remember, I was restless and eager to “go,” even if I didn’t know where I was going. I didn’t know what happened once my big sister disappeared on that huge, yellow bus; I just knew that I didn’t want to be not going.

It took my mother a few heartbreaks and several children before she found the man with whom she would live out the wedding vow “Till death do us part.” When I was around four years old, my mother met and married a man named Jerry Twain.

Jerry, an Ojibway Indian, was born and raised in the northern region of Ontario; his mother came from the Mattagami Indian Reserve and his father from the Bear Island Reserve in Temagami. Jerry had a bright, charming personality with a playful character and plenty of jokes and pranks up his sleeve. He had a particularly identifiable laugh that very visibly jerked his Adam’s apple up and down. He often cupped his hand over his mouth when he laughed hard from the gut, snorting and gasping for air through his fingers. He loved a good laugh. Jerry was generous and friendly, with a sharp mind and a witty sense of humor. A good friend of my mother’s named Audrey Twain had introduced her to Jerry, her younger brother.

My new stepdad was not much taller than my mother; around five foot ten—maybe five eleven if you include his thick brush of black hair. Jerry had a sort of unidentifiable, almost universal ethnic look about him, and I remember that he’d often joke about how when he’d met some people from Asia one time, they thought he was one of their own and started speaking to him in their native language—until they heard him reply in his local accent, with some th’s pronounced as t and pinched, long-held, almost sung vowels. He always got a kick imagining himself being mistaken for a Mexican, for example, or maybe someone from the Middle East. I recall seeing Saddam Hussein on the news for the first time years ago and thinking, Whoa, that guy looks so much like my dad! Although Jerry’s most prominent features were his dark skin, deep brown eyes, and black hair, one of his grandfathers, Luke, was of Scottish heritage, with blond, wavy hair and light blue eyes. Interestingly, I was told that my grandpa Luke had been raised on an Indian reservation from infancy. The dash of Caucasian physical traits showed up in Jerry’s light sprinkle of freckles on his face and especially in the texture of his kinky hair; he didn’t have the straight, shiny locks usually associated with Native North Americans. Other than his waves and the few freckles, though, he looked very obviously ethnic. The question was of which origin. Carrie and I both agree that he resembled George Jefferson from the comedy series The Jeffersons. Not only did his looks remind us of our dad, but they also shared the same quirky humor.

We all moved to a moderately small split-level rental house on Norman Street, in Timmins, similar in size to my grandma Eileen’s farmhouse, only with a more open concept, with a combined kitchen and living area. However, the living room was a couple of steps below the kitchen, which added several feet to the ceiling and made the home seem more spacious than it actually was. The Norman house sat on a residential street, just outside of the town center, and our house was one of the many small houses spaced about twenty feet apart that lined the street on either side. Most houses in Timmins are two-by-four timber-framed construction and average about a thousand square feet, with three bedrooms, one bathroom, and a basement. Compact homes are more the norm for practical reasons, as they’re more efficient for insulating and heating during the cold winters. Timmins was historically a gold mining town. It has a wide river running along its banks called the Mattagami, where the loggers used to send tons of raw cut logs down the current to the mills. Logging is still a part of the area’s industry, but the felled trees are now hauled by transport trucks to the lumberyards. Mining and forestry are the primary industries in the region, and Timmins’s population has grown from 29,000 in the sixties to around 43,000 today.

Our grandmother moved with us to the Norman house. Jerry didn’t resent having his new mother-in-law under the same roof as his new family. Far from it. He loved my grandma Eileen for her kind, nurturing, honest nature (to say nothing of her scrumptious pies). “She is a saint,” he used to say.

I have some vivid memories from the Norman house, like my first dishwashing lesson. My grandmother propped me up on a stool and let me make a sudsy, wet mess at the kitchen sink, basically. The first fighting I remember between my mom and Jerry also occurred in the Norman house. I don’t recall my grandmother ever being home when they fought, and I never heard her comment about it. It’s hard to imagine, though, that she was not aware of the violence, as she and my mother were so close and there would have been the obvious physical signs of bruising and soreness. My father had only good things to

say about my grandma Eileen and I only ever saw her be kind to him, regardless of what she knew, thought, or may have felt about his relationship with her daughter. Although she never expressed it in front of us children, I can only assume it would have disturbed her deeply to know it was an abusive relationship.

One fight between my parents that happened in the Norman house stands out as especially vivid. I don’t remember the exact cause, but these episodes tended to follow a familiar pattern. My father had a fairly jealous streak, so it could have been related to that. Or it’s likely that my mother might have been nagging him about not having enough grocery money, something we were beginning to experience more frequently. That was the source of most of their conflicts. Jerry wasn’t lazy—he always worked—but I’m not even sure if he had his full high school education, so he was limited to working for minimum wage, although he changed jobs frequently in search of a fatter paycheck. But bills still never seemed to get paid on time. We moved a lot, often because we couldn’t pay the back rent on one place, so we’d start over at another address until we fell too far behind there. It was a perpetual cycle, moving in order to run away from bills my parents couldn’t pay.

My mother pressured my father hard when he couldn’t provide. Now, it was stressful enough on him to know that he couldn’t make ends meet for his family of five, let alone having my mother nag him about it to no end. But to be fair, she had nowhere else to vent her anxiety and frustration. It was humiliating to have to go to friends or family for help; that was a last resort reserved for moments of absolute desperation.

From This Moment On

From This Moment On